East Africa (1252–1395 CE): Swahili Zenith and …

Years: 1252 - 1395

East Africa (1252–1395 CE): Swahili Zenith and the Interior Monarchies

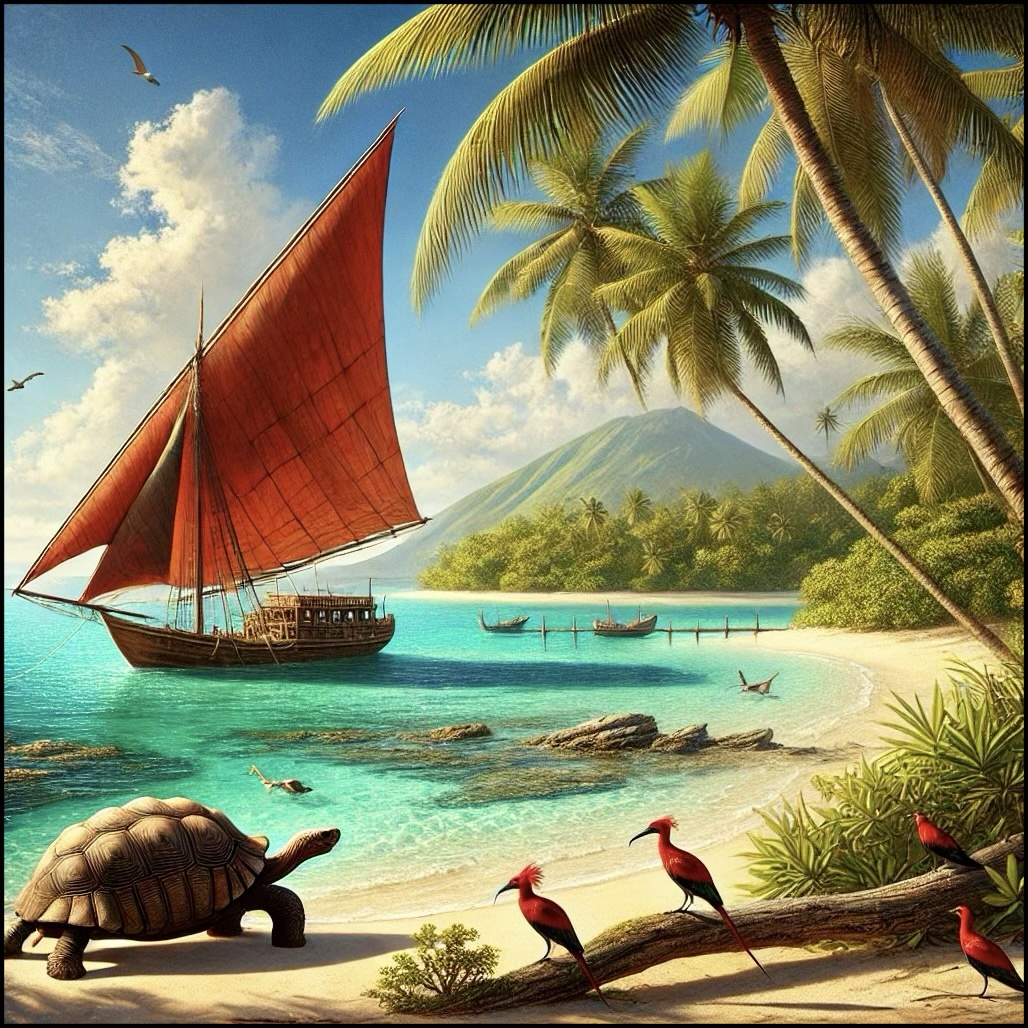

From the coral-stone harbors of Kilwa and Mombasa to the terraces of Ethiopia and the lakes of Uganda, East Africa in the Lower Late Medieval Age reached an extraordinary balance between coastal cosmopolitanism and interior consolidation. It was an age of gold and ivory, of sacred kingship and oceanic trade, when the Swahili city-states stood at their height, and inland monarchies linked Africa’s heartlands to the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The onset of the Little Ice Age around 1300 brought cooler temperatures and uneven rainfall across the region.

Uplands in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Zambia experienced occasional droughts, but the Great Lakes basins and monsoon-fed coasts provided stability.

The Indian Ocean moderated extremes—its monsoon cycles continuing to sustain fisheries, mangroves, and maritime provisioning. Madagascar’s diverse microclimates buffered global shifts, while the Seychelles and Mascarene Islands, still uninhabited, marked the farthest edges of African navigational knowledge.

The Maritime World: Swahili Cities and Oceanic Networks

Along the coast, the Swahili city-states—Kilwa, Mombasa, Malindi, Zanzibar, Pemba, Mafia, and Sofala—entered their golden age. Built of coral stone and lime plaster, ornamented with arches and carved doors, these cities were both mercantile ports and centers of learning. Kilwa Sultanate, under the Shirazi dynasts, reached its apogee in the fourteenth century, controlling the gold trade from Sofala and issuing its own coinage.

Merchants from Arabia, Persia, India, and even China exchanged gold, ivory, and slaves for cotton textiles, beads, porcelain, and horses. The city’s Friday mosques, minarets, and madrasas stood as emblems of Islamic piety and cosmopolitan taste.

Mombasa and Malindi developed rival alliances—one leaning toward Arabia, the other toward Asia—while Zanzibar and Pemba became twin centers for clove, ivory, and fish exports.

To the south, the harbors of Sofala received caravans from Great Zimbabwe, turning the plateau’s gold and ivory into coin and cloth.

Across the Mozambique Channel, Madagascar’s coastal settlements prospered through exchange with Swahili and Comorian merchants. The Sakalava and Merina polities expanded along river valleys, supplying rice, cattle, and slaves to the western Indian Ocean world. The Comoro Islands—Anjouan, Mohéli, Grande Comore, and Mayotte—emerged as small Islamic sultanates, their dynasties tracing both Arab and African ancestry. The Seychelles and Mascarene Islands, while uninhabited, appeared in navigators’ lore as provisioning and celestial landmarks, known to mariners from Kilwa to Calicut.

The Interior: Monarchies and Highland Realms

In the highlands to the north, the Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia, founded by Yekuno Amlak in 1270, restored Christian kingship after the Zagwe period. Claiming descent from Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, the new rulers shifted their capital toward the Amhara highlands, where terrace agriculture, irrigation, and monastic estates sustained both population and faith. Under Amda Seyon I (r. 1314–1344), Ethiopia expanded its influence eastward and southward, securing Red Sea access through Massawa and Zeila. Churches hewn in rock and crowned with domes of stone reflected the blending of Old Testament symbolism and African craftsmanship.

Farther west and south, along the Upper Nile and Great Lakes, new kingdoms consolidated.

In the interlacustrine region, the states of Buganda, Bunyoro, Rwanda, and Burundi took form, centered on royal courts whose power rested on sacred kingship (mwami, mukama).

These monarchies combined clan federation with centralized authority, legitimized through rituals of fertility, rain, and cattle sacrifice. Lake fisheries and banana groves provided surplus, while ironworking and canoe-building supported trade along the Victoria, Albert, and Tanganyika basins.

In the South Sudanese plains, Nilotic cattle peoples—the Dinka, Nuer, and Shilluk—expanded their pastures along the White Nile, where cattle herds served as both currency and cosmology. Chiefs derived prestige from rainmaking and sacrificial rites that linked herds to ancestors and the divine.

To the south, across the Zambezi Plateau and northern Zimbabwe, agricultural and copper-producing communities formed the northern hinterlands of Great Zimbabwe’s trade network. Zambia’s copper mines and the northern Zimbabwe–Mozambique corridor supplied ivory, cattle, and metal goods to caravans bound for Sofala and Kilwa, integrating the interior economies with the maritime sphere.

Trade and Exchange

Three great arteries tied East Africa together: the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Zambezi Valley.

-

From Massawa and Zeila, Ethiopian ivory, salt, and slaves reached Cairo and Aden.

-

Along the coast of Azania, Swahili and Indian merchants carried textiles, glass, and porcelain to inland markets.

-

Through the Zambezi corridor, gold, copper, and cattle flowed north and east, linking the Great Lakes and Zimbabwean plateau to the sea.

Caravan and canoe networks connected lake to coast, while monsoon winds timed annual voyages between Kilwa, Aden, and Calicut. Cowrie shells from the Maldives served as small currency from Sofala to Buganda, symbolizing the region’s integration into the wider Indo-Oceanic economy.

Belief and Symbolism

Islam provided the intellectual and architectural framework of the Swahili coast and the Comoros. Coral mosques, geometric calligraphy, and waqf endowments expressed the faith’s endurance.

In Ethiopia, Christianity defined kingship through its Old Testament lineage, while monasteries and saints’ cults shaped art, literature, and education.

Across the Great Lakes, divine kingship fused ancestral and fertility cults, affirming social cohesion through ritual.

Nilotic herders worshiped cattle as spiritual intermediaries; among them, rain shrines and ancestor altars ensured balance with the natural world.

Meanwhile, Madagascar’s highland peoples maintained ancestor worship, while coastal Malagasy blended it with Islamic influences, invoking both spirits and Allah at communal ceremonies.

Adaptation and Resilience

Ecological diversity was East Africa’s greatest defense against climate variability. Terraced fields in the Ethiopian highlands, banana groves in the Great Lakes, floodplain fisheries along the Nile, and oceanic provisioning along the Swahili coast created overlapping zones of surplus.

When drought struck the interior, coastal ports imported grain; when plague thinned the Red Sea trade, Zambezi and lake routes compensated.

The region’s multi-corridor structure—maritime, fluvial, and caravan—ensured continuity even amid shifting monsoons.

Monastic and clan institutions, bound by ritual law and kinship, preserved social stability through spiritual sanction and redistribution of goods.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, East Africa had achieved a high degree of integration across its coast and interior.

The Swahili city-states stood as architectural jewels and maritime hubs linking Africa, Arabia, India, and China.

The Solomonic kings of Ethiopia reestablished a Christian empire that tied the highlands to the Red Sea and the Holy Land.

The Great Lakes monarchies matured into enduring polities, blending sacred kingship with clan-based consensus.

Nilotic herders and Zambezi farmers continued to sustain and supply the coastal trade networks, while Madagascar and the Comoros anchored the western Indian Ocean world in cultural and ecological diversity.

Through monsoon trade, sacred kingship, and environmental adaptation, East Africa emerged by the close of the fourteenth century as a cosmopolitan corridor—its architecture, faiths, and economies bound together by the rhythm of rain, river, and sea.

Maritime East Africa (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Bantu peoples

- Arab people

- Omanis

- Somalis

- Madagascar

- Nilotic peoples

- Sakalava people

- Merina people

- Swahili people

- Comoro Islands

- Islam

- Abbasid Caliphate (Baghdad)

- Kilwa Sultanate

Topics

Commodoties

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Slaves

- Spices