Southeast Europe (1540–1683 CE) Ottoman Consolidation, …

Years: 1540 - 1683

Southeast Europe (1540–1683 CE)

Ottoman Consolidation, Venetian Crossroads, and the Awakening of Balkan Identities

Geography & Environmental Context

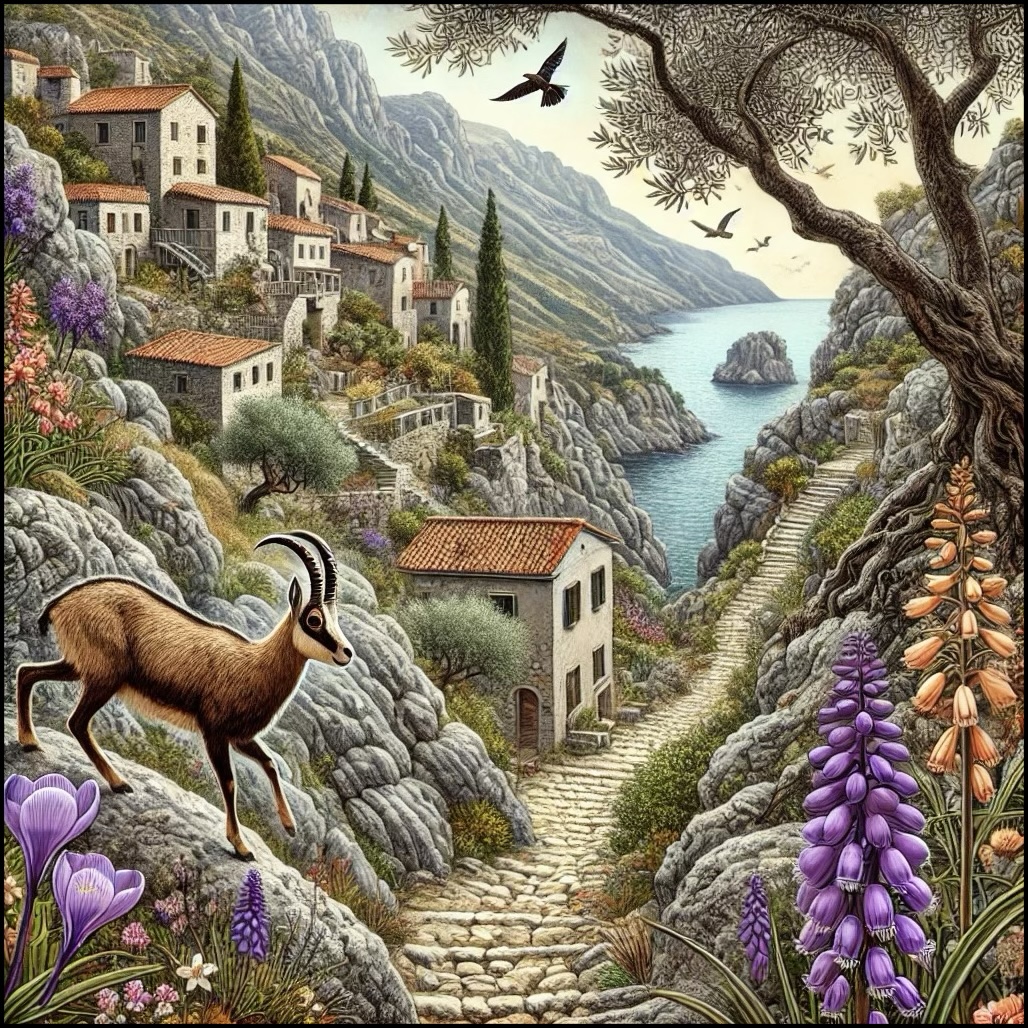

Southeast Europe stretched from the Danube and Black Sea plains to the Aegean and Adriatic coasts, encompassing the lands of modern Greece, Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania, and Moldova. The region’s mountains, river valleys, and island coasts formed both natural barriers and corridors for empire. Ottoman rule dominated most of the Balkans, while Venice held the maritime fringe of Dalmatia, the Ionian Islands, and Crete, and the Habsburgs fortified northern Croatia and Slovenia.

The Little Ice Age brought alternating droughts and floods that shaped agricultural rhythms. The Danube basin saw both bountiful grain harvests and years of devastation, while earthquakes and epidemics—especially plague—were recurrent features of life.

Settlement and Subsistence Patterns

Rural continuity and imperial integration defined the era. Ottoman demographic policy resettled Anatolian Muslims in key zones such as Thrace, Bulgaria, and the lower Danube, reinforcing administration and Islamization. Yet, in the mountainous Balkans, isolated Orthodox and Catholic villages preserved pre-Ottoman languages, customs, and religious networks.

-

Plains & Valleys: Wheat and barley dominated; in southern regions, vines, olives, and figs sustained local economies.

-

Highlands: Transhumant herding of sheep and goats spanned the Dinaric and Pindus ranges.

-

Coasts: Dalmatian ports and the Aegean islands traded wine, olive oil, salt, and timber through Venetian and Ottoman markets.

-

Urban Centers: Thessaloniki, Sarajevo, Skopje, and Sofia grew under Ottoman patronage; Dubrovnik (Ragusa) remained an autonomous maritime republic balancing between empires.

Political Dynamics

Ottoman Administration and Expansion (1540–1580)

Under Suleiman the Magnificent and his successors, Ottoman authority deepened through provincial reorganization. The empire’s sanjak and eyalet system strengthened taxation and defense, while governors (pashas) oversaw garrisons, bridges, and caravan routes.

Regional Resistance and Fragmentation (1580–1620)

Rising taxation and conscription pressures fostered local revolts. Michael the Brave (1593–1601) briefly united Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania, symbolizing early Romanian national consciousness. In Serbia and Bulgaria, hajduk (bandit–rebel) groups emerged as popular symbols of resistance.

Internal Rivalries and Imperial Strain (1620–1683)

Administrative corruption, Janissary unrest, and declining central control weakened the empire’s Balkan provinces. Rivalries among the Wallachian and Moldavian princes—such as Matei Basarab and Vasile Lupu—reflected both cultural vitality and political fragmentation. The Habsburg frontier hardened in Croatia and Hungary, as border fortresses became permanent military zones.

Economic & Technological Developments

Trade and Prosperity (1540–1600)

Ottoman stability encouraged trade: improved roads, caravanserais, and bridges linked Constantinople, Belgrade, and Buda. Aleppo and Thessaloniki tied the Balkans to the Levant, while Venetian and Ragusan ships distributed Balkan grain, leather, and wax through the Adriatic.

Economic Contraction (1600–1683)

Fiscal strain, warfare, and climatic stress caused agricultural decline and depopulation. Over-taxation and currency debasement drove peasants from fertile valleys into marginal lands. Still, small centers like Chiprovtsi in Bulgaria sustained metalwork and trade, and monastic estates remained key local employers.

Cultural & Religious Life

Imperial Patronage and Artistic Synthesis

Ottoman mosques, bridges, and markets transformed Balkan cities. The Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque in Sarajevo and Skopje’s Stone Bridge embodied Islamic civic ideals fused with Byzantine craftsmanship. Venetian coastal towns—Split, Zadar, Corfu—adopted Renaissance and Baroque architecture, standing as contrasts to Ottoman domes inland.

Faith, Identity, and Education

The millet system allowed Orthodox, Catholic, and Jewish communities relative autonomy. Orthodox monasteries—Rila, Peć, Hilandar, Agapia—became bastions of learning and manuscript copying. Catholic orders, especially Franciscans in Bosnia and Jesuits in the Adriatic hinterland, fostered literacy and Counter-Reformation ties. Religious identity increasingly shaped political consciousness: Orthodoxy underpinned Bulgarian, Serbian, and Romanian cultural endurance, while Catholic enclaves in Dalmatia and Croatia gravitated toward Venice and Rome.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Terracing and irrigation maintained agriculture on rugged slopes.

-

Pastoral migration across mountains ensured protein and trade goods.

-

Diversification—combining fishing, viticulture, and artisanal crafts—provided stability during poor harvests.

-

Communal networks—guilds, monastic charities, and village assemblies—managed relief and reconstruction after famine or plague.

Political & Military Shocks

-

1571: Venetian Cyprus falls to the Ottomans; the same year, the Battle of Lepanto halts Ottoman naval supremacy.

-

1593–1606: The Long Turkish War drains imperial coffers.

-

1648–1669: The Cretan War (Siege of Candia) pits Venice and the Ottomans for Crete, influencing western Balkan militarization.

-

1683: The Ottoman Siege of Vienna—launched through Balkan corridors—fails, marking the start of Ottoman territorial retreat in Europe.

Transition

Between 1540 and 1683, Southeast Europe remained an imperial hinge and a laboratory of coexistence. Ottoman administration integrated the Balkans into the empire’s fiscal and cultural systems; Venetian coasts and Habsburg frontiers kept European influences alive. Local societies balanced submission and resilience: monasteries preserved language and scripture; hajduks and mountain clans nurtured myths of defiance.

By the time the Ottoman armies failed at Vienna in 1683, the region’s political geography was poised for transformation. The seeds of Balkan national consciousness—rooted in faith, language, and memory—were germinating beneath the structures of empire, setting the stage for the long 18th-century unraveling of Ottoman dominance in Europe.

Western Southeast Europe (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Slavs, South

- Greeks, Medieval (Byzantines)

- Venice, Duchy of

- Croats (South Slavs)

- Serbs (South Slavs)

- Croatia, Kingdom of

- March of Carniola

- Habsburg, House of

- Christians, Eastern Orthodox

- Christians, Roman Catholic

- Dalmatia region

- Croatia, Kingdom of

- Austria, Archduchy of

- Styria, Duchy of

- Athens, Duchy of

- Epirus, Despotate of

- Serbia, Kingdom of

- Hungary, Kingdom of

- Achaea, Principality of

- Achaea, Principality of

- Ottoman Emirate

- Catalan Company of the East, Grand (officially the Company of the Army of the Franks in Romania, sometimes called the Grand Company and widely known as the Catalan Company

- Ottoman Emirate

- Serbian Empire

- Ottoman Empire

- Epirus, Despotate of

- Ragusa, Republic of

- Carniola, Duchy of

- Humska zemlja (Hum)

Topics

- Little Ice Age, Warm Phase I

- Little Ice Age (LIA)

- Black Death, or Great Plague

- Serbian Empire, fall of the

- Kosovo, Battle of

Commodoties

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Beer, wine, and spirits

- Manufactured goods

- Money

- Aroma compounds